We explore the theological significance of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael within Catholic eschatology. Drawing on Scripture, the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC), and the writings of the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, it considers the angelic hierarchy, the nature of eternity, and the distinction between angelic and human modes of existence. The analysis situates each Archangel’s mission—defense, proclamation, and healing—within the larger mystery of redemption and resurrection, concluding with reflections on how angels and saints participate together in the eternal life of God.

Introduction

In Catholic tradition, the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael stand as luminous guardians and messengers at the threshold of eternity. Their appearances in Scripture, tradition, and liturgy invite us not only to venerate their personhood but to reflect on their roles in our journey toward resurrection. This article explores the theology of these three Archangels, their functions in the afterlife, and corrects a common misconception: that human souls transmogrify into angels. Through Scripture, the Catechism, and patristic authority, we will uncover how Michael defends, Gabriel proclaims, and Raphael heals — and how, in the eschaton, the interplay of angels and saints testifies to God’s victory over death.

The Presence of the Archangels in Salvation History

The feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael on 29 September celebrates God’s invisible agents of mercy and justice. In Scripture, these three Archangels appear at pivotal moments: Michael in combat with the dragon (Rev 12:7–9), Gabriel announcing the Incarnation (Luke 1:26–38), and Raphael healing and guiding the family of Tobit (Tobit 12:15). Their missions, though distinct, converge in a single salvific purpose—to assist humanity on the journey from fall to resurrection.

“Are they not all ministering spirits sent forth to serve, for the sake of those who are to obtain salvation?” (Heb 1:14, ESV).

II. The Nature of Angels and Archangels in Catholic Doctrine

The Catechism (CCC 328–336) teaches that angels are purely spiritual beings, personal and immortal, surpassing all visible creatures in perfection. Created before humanity (Col 1:16), they possess intellect and will but no material body. Because time measures material change, they are not bound by time’s sequence.

The angelic hierarchy, articulated by Pseudo-Dionysius and confirmed by Gregory the Great in Moralia in Job, consists of nine choirs: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones; Dominions, Virtues, Powers; Principalities, Archangels, and Angels. “Archangels” (Greek arch-angelos, chief-messengers) hold a mediating role between the higher choirs and humanity.

Angels differ ontologically from humans. At death, the faithful do not become angels but saints (CCC 1023-1029). The human soul, though spiritual, remains ordered to the body and awaits resurrection. Angels, never embodied, serve God as messengers of His providence (CCC 329–331).

[Angels, Time, and Eternity — A Catholic Understanding]

When the Church teaches that angels exist outside of time, it means they are not bound by the ticking sequence of hours as we are. Time measures change in matter, but angels have no bodies—they are pure spirits (CCC 330).

Their existence is described as aeviternity, a created form of eternity. Unlike us, angels do not move from moment to moment; they see reality in a single act of understanding (Aquinas, ST I q.10; q.58).

God alone is eternal—entirely beyond time. Angels share that timelessness as creatures who can act within time but are not confined by it. They stand, so to speak, on the riverbank of time, seeing its whole course, while we float within its current.

When we enter heaven, we will not become angels, but like them we will step into God’s eternal “now.” Eternal life is not endless minutes; it is the fullness of being, where every act of love and worship is present at once in the light of God.

“Your today is eternity itself.” — St. Augustine, Confessions XI

III. St. Michael the Archangel — Defender of Souls and Guardian of the Church

Scriptural foundations. Michael’s appearances frame salvation history.

- Daniel 12:1 calls him “the great prince who has charge of your people.”

- Revelation 12:7–9 depicts him leading the heavenly hosts against the dragon.

- Jude 1:9 shows him contending for the body of Moses.

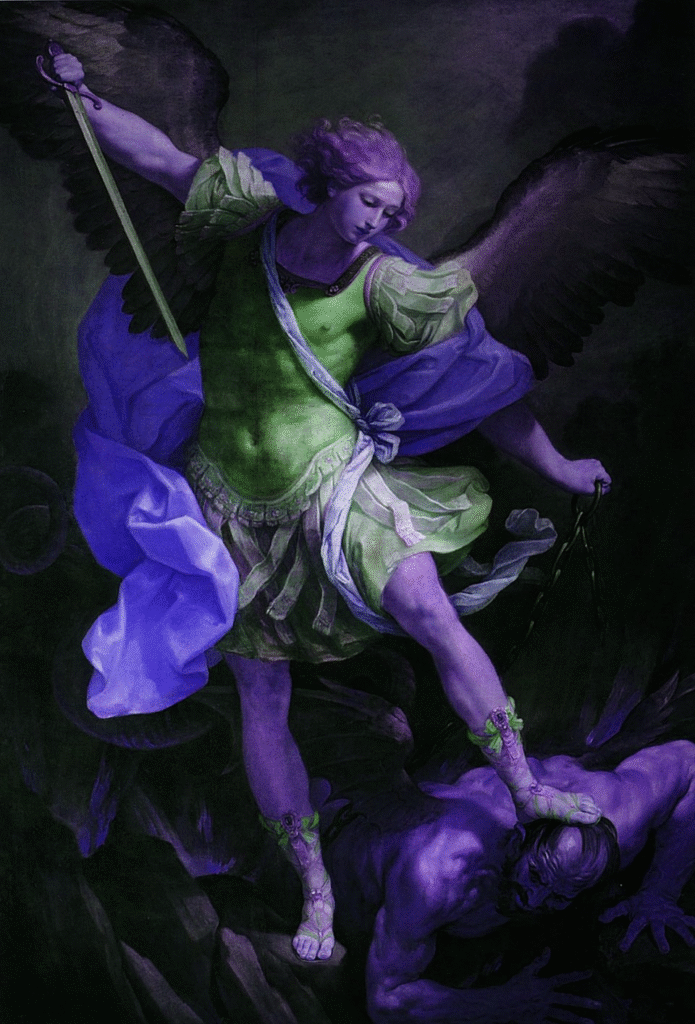

Theological role. Michael embodies divine justice and protection. In the Roman Ritual and Funeral Liturgy, the Church invokes him to escort souls to paradise: “May Michael the Archangel lead you into the holy light.” (Libera me, Domine). He thus serves as defender against evil at death and intercessor at judgment.

Patristic insight. St. Gregory the Great explains that Michael’s name—“Who is like God?”—is itself a declaration of divine supremacy (Homilies on the Gospels 34). Aquinas (1265/1947, ST I q.108 a.8) affirms Michael’s leadership of the angelic militia. Catholic eschatology associates him with the defense of the soul in its final combat and with the ultimate defeat of Satan (Rev 20:10).

Figure 1 : Guido Reni, St Michael Vanquishing Satan (1636), Public Domain.

IV. St. Gabriel the Archangel — Herald of Divine Life and Resurrection

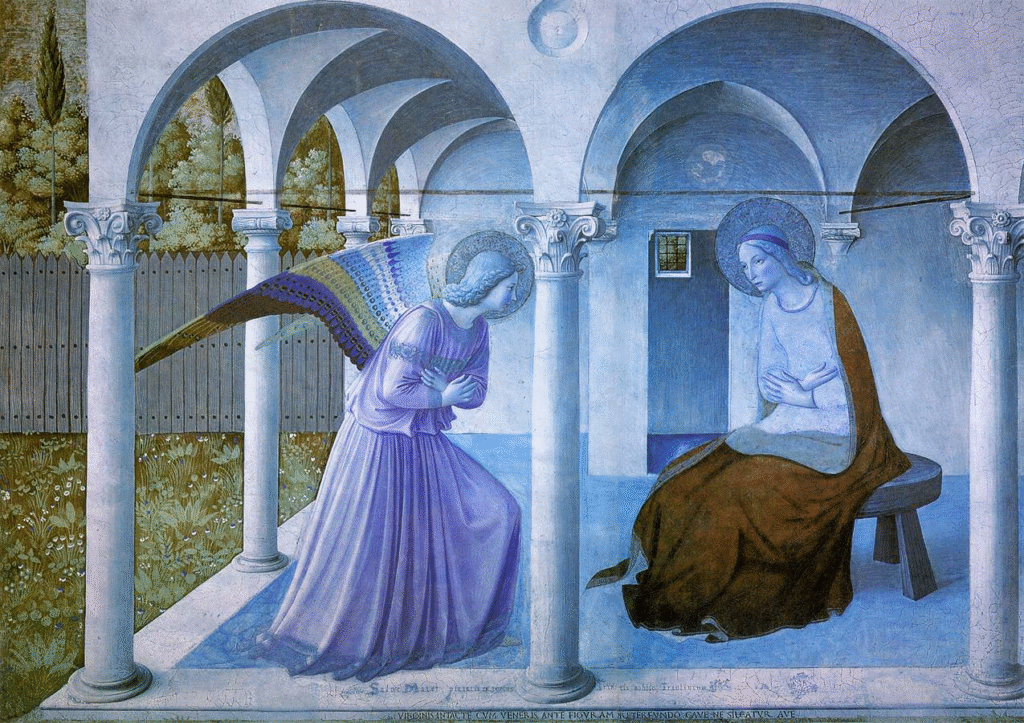

Scriptural foundations. Gabriel appears in Daniel 8–9, interpreting visions of restoration, and in Luke 1:19, 26–38, announcing the births of John the Baptist and of Christ.

Theological significance. Gabriel inaugurates the mystery of the Incarnation—“The Holy Spirit will come upon you” (Luke 1:35)—and thereby the possibility of resurrection itself. He links prophecy and fulfillment, promise and realization.

Patristic insight. St. Bernard of Clairvaux called Gabriel the “angel of the Incarnation,” noting that the same messenger who announced Christ’s conception proclaimed His resurrection to the women at the tomb.

Liturgical role. Gabriel symbolizes divine revelation and enlightenment. In the resurrection narrative (Matt 28:2-6), the angel who rolls away the stone continues Gabriel’s mission of proclaiming life’s victory over death.

Figure 2 : Fra Angelico, The Annunciation (c. 1430-1432), Public Domain.

V. St. Raphael the Archangel — Healer and Guide of the Faithful

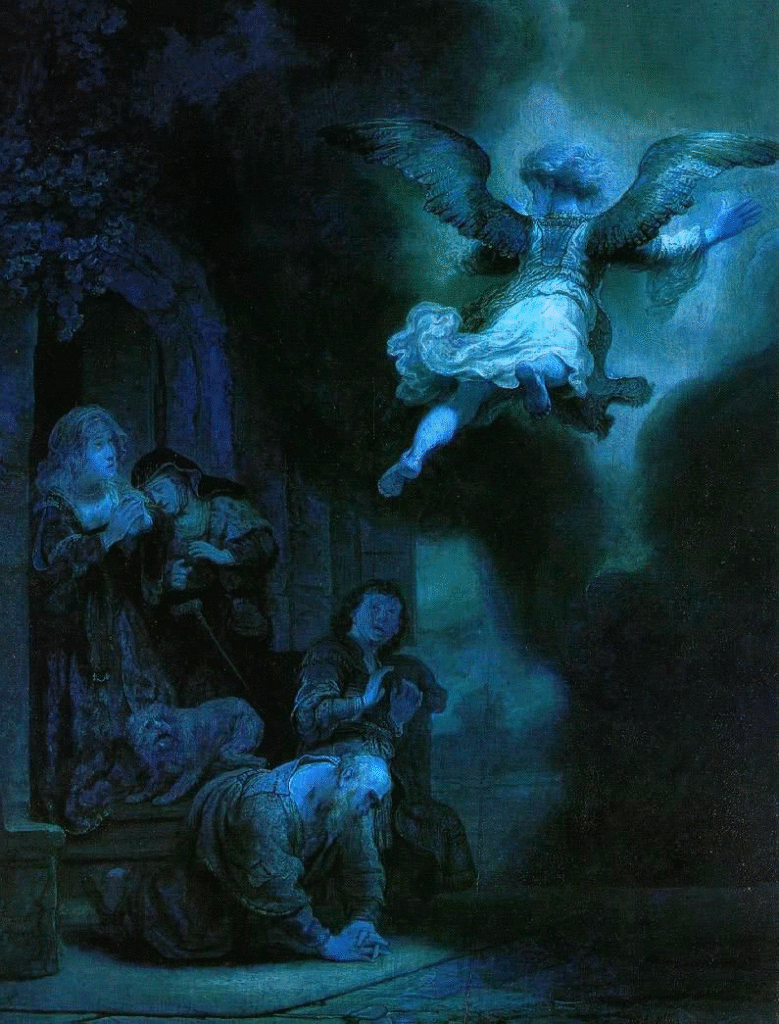

Scriptural witness. In the Book of Tobit, Raphael reveals himself: “I am Raphael, one of the seven who stand before the Lord” (Tobit 12:15). He guides Tobiah, heals Tobit’s blindness, and frees Sarah from a demon.

Theological meaning. Raphael’s very name means “God heals.” His ministry prefigures Christ’s redemption—the healing of sin’s blindness and the liberation of the soul. He represents divine mercy accompanying humanity on its pilgrimage toward eternal life.

Patristic commentary. St. Augustine, City of God (426, Bk 9), associates Raphael with the healing grace that restores creation. As Michael defends and Gabriel proclaims, Raphael restores — all three foreshadow the Resurrection’s wholeness: victory, illumination, and healing.

Figure 3. Rembrandt, The Archangel Raphael Leaving the Family of Tobit (1637). Public domain.

VI. Humans and Angels in the Afterlife: Clarifying the Distinction

A persistent popular misunderstanding holds that people become angels when they die. Catholic doctrine rejects this: angels and humans are distinct orders of creation (CCC 330, 1023–1029).

Scriptural clarity.

- Matthew 22:30 — “They neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven.” “Like” describes immortality and purity, not identity.

- Hebrews 12:22–23 separates “innumerable angels” from “the spirits of the righteous made perfect.”

- 1 Corinthians 15:42–44 portrays the resurrected body as imperishable yet still human.

Theological precision.

Aquinas explains that because the human soul is naturally united to a body, its perfection is resurrection, not transformation into another species (ST I q. 108 a. 8). The Incarnation confirms this dignity: God assumed human, not angelic, nature. Therefore, in glory, redeemed humanity participates in divine life in a way that even the angels marvel to behold.

VII. The Communion of Saints and Angels

In heaven, saints and angels form one chorus of worship (CCC 336; Rev 5:11–13). Angels serve; saints share in divine filiation. Both contemplate the same Word. The Church on earth already shares in this communion through liturgy: every Mass invokes angels and saints together—“and so, with Angels and Archangels…”—prefiguring the eternal praise of heaven.

VIII. The Archangels and the Resurrection Narrative

At the Resurrection, angels act as heralds of divine victory:

- Matthew 28:2–6 — an angel rolls back the stone: “He is not here; for He has risen.”

- John 20:12 — two angels appear in the tomb, where the body of Jesus had lain.

These fulfill the missions of the three Archangels:

- Gabriel’s voice of announcement echoes in the angel’s proclamation.

- Michael’s guardianship surrounds the empty tomb, symbolizing the defeat of death.

- Raphael’s healing ministry culminates in Christ’s triumph, the restoration of creation itself.

IX. Eschatological Hope: Angels in the Final Judgment

Christ foretold that angels will accompany Him at the end of time: “He will send out His angels with a loud trumpet call, and they will gather His elect” (Matthew 24:31). Daniel 12:1 again names Michael as protector of God’s people; Matthew 13:49 pictures angels separating the righteous from the wicked. Yet the role of Judge belongs to Christ alone (John 5:22).

Catholic eschatology sees in the angels’ participation a sign of ordered harmony: they execute divine justice, while saints, united to Christ, rejoice in the consummation of redemption.

X. Conclusion — Messengers of the Resurrection

The Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael manifest God’s fidelity to creation.

- Michael defends the soul and the Church from evil.

- Gabriel heralds divine life and resurrection.

- Raphael heals and restores.

Together they mirror the Paschal Mystery: victory, revelation, and healing. They remind the faithful that God’s providence attends every stage of existence—from birth to death, from judgment to resurrection.

When we die, we do not become angels; we become what angels delight to serve—saints, resurrected in Christ and beholding the face of God.

“Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father.” (Matt 13:43)

Angelic Ontology and Catholic Doctrine

The Nature and Purpose of Angels

Angels, according to Catholic doctrine, are purely spiritual beings, created by God with intellect and will but without physical bodies. They are personal, immortal, and surpass all visible creatures in excellence (Catechism of the Catholic Church [CCC] 328–336).

- They exist outside of time (cf. Hebrews 1:14).

- They serve God’s providence and act as “ministering spirits sent forth to serve, for the sake of those who are to obtain salvation” (Hebrews 1:14, ESV).

Angels are distinct from humans in their nature and purpose (CCC 330). Human beings, created body and soul, are destined for resurrection; angels, never embodied, do not share that fate.

Hierarchies and the Title “Archangel”

Catholic tradition holds that angels are organized into a hierarchy of nine choirs, and among them, certain angels are designated “Archangels” — leaders or messengers entrusted with special missions to humanity (cf. St. Gregory the Great, Moralia in Job). The Catechism does not list nine choirs explicitly but affirms that some angels are sent as messengers with particular roles (CCC 329–331).

The term “archangel” appears in Scripture:

- Michael is called an archangel in Jude 1:9.

- No other angel is explicitly denominated archangel, but Gabriel and Raphael, by tradition and usage, are accorded that title due to the magnitude of their Scriptural missions.

Thus, the Archangels participate in angelic ministry in an elevated manner, particularly as mediators in salvation history.

St. Michael: Defender, Judge, Protector

Scriptural Foundations

Michael is the principal Archangel with notable apocalyptic and angelic warfare roles:

- Revelation 12:7–9 (ESV) — “Now war arose in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon… and the dragon was defeated.”

- Daniel 12:1 — “At that time shall arise Michael, the great prince who has charge of your people.”

These passages situate Michael as a cosmic defender of souls and a heavenly champion in spiritual conflict.

Theological Role in the Afterlife

Michael’s role as a psychopomp — one who escorts souls — emerges in Catholic liturgical prayers. In the Roman Ritual (Order of Christian Funerals), the prayer “May Michael the Archangel lead you into the holy light” (from the Libera me, Domine) invokes him directly at the moment of judgment.

His function encompasses:

- Defense against evil and demonic assault at the hour of death.

- Intercessory role before God on behalf of the faithful.

- Symbolic participation in the final judgment, echoing Christ’s victory over Satan.

The traditional Supplication of St. Michael (e.g., “St. Michael the Archangel, defend us in battle…”) further underscores his ongoing spiritual guardianship of the Church.

Patristic and Scholastic Insights

St. Gregory the Great interprets Michael’s name — “Who is like God?” — as a rebuke to pride and as a divine defender (Gregory, Homilies on the Gospels 34).

In the Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas Aquinas (1265/1947) treats Michael as the head of the angelic militia (ST I, Q. 108, a. 8) and affirms his role in spiritual conflict and guardianship of the Church.

Michael’s presence at death and his cosmic role reflect the doctrine that spiritual warfare continues beyond mortal life, and the soul requires a protector before the divine tribunal.

St. Gabriel: Herald of Promise and Resurrection

Scriptural Appearances

Gabriel performs a dual role: as executor of prophecy and announcer of the Incarnation:

- Daniel 8:16 and 9:21 — Gabriel interprets visions concerning Israel’s restoration.

- Luke 1:19, 1:26–38 — Gabriel announces both John the Baptist’s birth and Christ’s conception: “The Holy Spirit will come upon you…”

His mission links God’s promise to its fulfillment.

Gabriel’s Theological Significance

Gabriel initiates the decisive moment in salvation history: the Incarnation. By bringing God’s word into the world, Gabriel becomes the prelude to Christ’s resurrection. The angelic annunciation is not merely about birth, but about new creation.

Thus, Gabriel’s role in the afterlife context is anticipatory — as the one who broadcasts divine life, he foreshadows how, at resurrection, God will communicate the fullness of life to redeemed souls.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux praises Gabriel as the Angel of the Incarnation, observing that the same messenger who announced Christ’s birth would later herald His victory over death.

Tradition and Liturgy

While Gabriel is less invoked in funeral rites than Michael, he remains associated with revelation and illumination. In the eschatological perspective, he figures as the messenger who brings the final summons or proclamation of victory, much as he brought the first word of divine life to Mary.

St. Raphael: Healer and Companion on the Journey

Scriptural Witness: Tobit

Raphael is introduced in the Deuterocanonical Book of Tobit as a companion and healer:

- Tobit 12:15 — “I am Raphael, one of the seven angels who stand before the Lord.”

- He guides Tobiah, heals Tobit’s blindness, and expels the demon afflicting Sarah.

Raphael’s ministry is holistic — guiding, healing, and protecting.

Role in Eschatological Healing

In the afterlife, Raphael’s mission finds its fulfillment in the transformation of the redeemed:

- He prefigures clinical healing (Tobit) and spiritual restoration (sin’s cure).

- His name, Raphael, means “God heals,” signifying that resurrection is the ultimate healing of body and soul.

- The journey he guides in Tobit mirrors the pilgrimage of the soul from temporal exile to eternal communion.

St. Augustine, in City of God, underscores divine assistance through angelic mediation in man’s path toward salvation. Augustine associates Raphael with divine mercy, aiding creation in its brokenness (City of God, Book 9).

Humans, Angels, and the Afterlife: Clarifying the Distinction

A very common error in popular piety is to assume that, once we die, we somehow become angels. Christian tradition and doctrine consistently reject that.

Scriptural Clarification

- Matthew 22:30 (ESV) — “For in the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven.”

→ Notice: “like angels,” not “become angels.” - Hebrews 12:22–23 distinguishes “innumerable angels” from “the spirits of the righteous made perfect.”

- 1 Corinthians 15:42–44 speaks of the resurrection body: “It is sown perishable; it is raised imperishable. … It is sown in dishonor; it is raised in glory.”

Catechetical Explanation

The Catechism states (CCC 1023–1029) that at death souls enter judgment, await resurrection, and in glory become part of the “communion of saints.” Saints are not angels, but human beings redeemed by grace. CCC 334–336 treats angels as a separate order of creation.

Scholastic Theology

Thomas Aquinas argues in Summa Theologiae (I, Q. 108) that human beings can never become angels, because their natures are fundamentally different. The Incarnation shows that God intended to redeem humanity in its own nature, not to convert mankind into the angelic order.

Saints in heaven, then, are glorified human persons, not angels in disguise. They share eternal life, contemplation, and communion with God, but remain human (though transfigured).

The Communion of Saints and Angels

In heaven, angels and saints unite in a single purpose: the adoration of God. Angels act as messengers and servants; saints as witnesses to redemption.

- CCC 336: “From its beginning until death, human life is surrounded by their watchful care and intercession.”

- Revelation 5:11–13 portrays “myriads of angels” and “every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth” worshipping the Lamb together.

Thus, in the heavenly liturgy, angels and saints praise God in harmony — not as equals, but in complementary roles.

The Resurrection and the Archangels

When Christ rose, angels played prominent roles:

- In Matthew 28:2–6, an angel rolled back the stone and proclaimed, “He is not here, for he has risen.”

- In John 20:12, Mary Magdalene sees two angels inside the tomb.

These angelic presences echo the functions of Gabriel and Michael: announcing resurrection (Gabriel) and guarding victory (Michael). Raphael’s healing symbolism too is fulfilled as Christ heals the brokenness of sin and death.

In eschatological doctrine, Christ will send His angels to gather the elect (Matthew 24:31), Michael will again protect God’s people (Daniel 12:1), and angels will assist in the final judgment (Matthew 13:49). Yet Christ alone judges (John 5:22).

Toward an Eschatological Vision

In the final resurrection:

- Angels will accompany God’s call and execute divine judgment.

- The righteous will share in God’s life, transformed, glorified, renewed in body and soul.

- Saints will reign with Christ (cf. Revelation 20:4–6).

The Archangels stand as perpetual witnesses to the unfolding plan:

- Michael — our defender until the end, protector of the just

- Gabriel — the herald who bridges promise and fulfillment

- Raphael — the gentle healer whose mission is consummated in resurrection

The Christian hope is that the very God who dispatched these servants will one day welcome us into the light, where angels rejoice to see us restored and exalted.

🕊️ Angels, Eternity, and the “Outside of Time” Mystery

1. What the Church Means by “Outside of Time”

When Catholic teaching says angels exist outside of time, it doesn’t mean they live in an empty void or a frozen stillness. It means that they are not bound by time as we experience it.

Human beings live in chronological time — one moment follows another; we change, we grow, we forget, we anticipate. Our experiences unfold like a movie reel.

Angels, by contrast, are pure spirits (CCC 330). They have no bodies, and therefore no biological or material processes that require time to measure change. Time, in the physical sense, measures change in matter. Since angels don’t have matter, they experience existence in a different mode — a single, unified act of awareness rather than step-by-step succession.

“Their knowledge is not discursive like ours; they do not reason from premises to conclusions but see the truth instantly.”

— St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae (I, q.58)

So angels have what theologians call aeviternity — a kind of created eternity. It’s not the same as God’s eternity (which is absolutely timeless and infinite), but it’s beyond our temporal sequence.

2. Eternity, Aeviternity, and Time (in Simple Terms)

- Time = successive moments (humans live here).

- Aeviternity = created beings who are stable and changeless in essence but can still have choices or missions (angels and souls in heaven).

- Eternity = uncreated, absolute changelessness — God alone (Aquinas, ST I q.10).

Think of it like this:

Humans are in the river of time, floating downstream.

Angels stand on the riverbank, seeing the whole river at once.

God is above the entire landscape — He made both the river and the banks.

That image helps explain why angels can appear “in” our time (to deliver a message, protect, or heal) while not being bound to it. They can “step into” a moment because their perception isn’t limited to one.

3. Connection to the Catholic View of Eternal Life

When Catholics speak of eternal life, we don’t mean endless minutes that never end; we mean entry into God’s eternal “now.”

In heaven, we too will step out of chronological time and into participation in God’s eternity — we will see all things in the divine light, not in temporal sequence. The beatific vision (CCC 1023) is instantaneous and total — no waiting, no forgetting, no before or after.

That’s why Aquinas says the blessed are “in aeviternity” too, like the angels — creatures, but sharing God’s eternal stability (ST I q.10 a.5).

4. Eternalism and Catholic Thought

Philosophically, “eternalism” (as discussed in modern metaphysics) holds that all moments of time — past, present, future — equally exist. Catholic theology partially echoes this in saying that to God, all times are present:

“God’s eternal ‘now’ embraces all time as present to Him.”

— CCC 600

However, the Church distinguishes between God’s knowledge of all times (which is absolute) and our participation in time. Angels, being spiritual, live closer to that divine perspective — they see reality as a whole picture, not as a moving timeline.

So, while Catholic theology doesn’t adopt “eternalism” in the strict philosophical sense, it shares its insight that time is not ultimate reality — eternity is.

5. How to Explain This Simply to a Lay Reader

Imagine a stained-glass window lit from behind.

- We, in time, see one color at a time as the sun shifts.

- Angels see the whole window all at once.

- God is the light that shines through it all.

That’s the difference between temporal, aeviternal, and eternal existence.

6. In the Afterlife

When we die and enter heaven, our souls will no longer experience the ticking of time. We will not become angels — but, like them, we will exist in the “eternal now” of God’s presence. Our resurrected bodies will still be material, yet glorified beyond corruption or decay — no aging, no waiting.

Thus, in the communion of saints, angels and humans share the same mode of eternity in their relationship with God, though not the same nature.

7. Summary for Catechetical Clarity

| Level | Mode of Being | Bound to Time? | Description |

| God | Eternity | No | Infinite, timeless; all moments equally “now.” |

| Angels / Blessed Souls | Aeviternity | Partially (missions in time) | Created beings outside chronological succession. |

| Humans (earthly) | Time | Yes | Bound to past–present–future sequence. |

8. Key Catechism & Theological Citations

- CCC 330: Angels are “spiritual, non-corporeal beings” with intelligence and will.

- CCC 1023: The blessed “live with Christ” and see God “as He is.”

- CCC 600: God’s eternal plan embraces all time as present to Him.

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I q.10: On eternity and aeviternity.

- St. Augustine, Confessions, Book XI: “Your today is eternity itself.”

References

Aquinas. (1265/1947). Summa Theologiae (I q. 10; I q. 58; I q. 108 a. 8). Benziger Bros.

Augustine. (426). City of God (Book 9). In Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Vol. II. T & T Clark.

Bernard of Clairvaux. (12th cent.). On the Annunciation. In J. Leclercq (Ed.), Cistercian Writings.

Catechism of the Catholic Church. (1997). Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

Gregory the Great. (6th–7th cent.). Homilies on the Gospels (Homily 34). In Patrologia Latina Vol. 76.

Holy Bible, English Standard Version. (2001). Crossway Bibles.

Pseudo-Dionysius. (5th cent.). Celestial Hierarchy. In The Complete Works (Colm Luibheid, Trans.). Paulist Press.

Roman Ritual. (1989). Order of Christian Funerals. International Commission on English in the Liturgy.

St. Gregory the Great. Moralia in Job. (Trans. H. Morley). Oxford University Press.

Shanaz Joan Parsan is a researcher and strategic financial leader whose academic interests include Catholic theology, philosophy of time, and the dialogue between faith and reason. Drawing on a lifelong devotion to the Catholic intellectual tradition, her writing seeks to bridge scholarly depth with contemplative faith, illuminating how doctrine, Scripture, and lived spirituality converge in the mystery of redemption.