By Shanaz Joan Parsan

Abstract

This paper critically examines Norman A. Klotz’s Prayers of the Cosmos, particularly his rendering of the Lord’s Prayer. While Klotz presents his work as a rediscovery of Jesus’ Aramaic spirituality, his interpretations significantly depart from the authentic Syriac Peshitta text and the Catholic theological tradition. Through philological, doctrinal, and philosophical analysis, this critique demonstrates that Klotz’s translations distort the original Christological and Trinitarian meanings of the prayer, replacing them with a syncretic cosmology incompatible with Catholic orthodoxy.

1. Introduction

Interest in Aramaic versions of Christian scripture has grown in recent decades, especially among those seeking mystical or universal interpretations of Jesus’ teachings. One of the most influential examples is Norman A. Klotz’s Prayers of the Cosmos (1990), which presents poetic renderings of the Lord’s Prayer based on speculative Aramaic roots. Although Klotz’s project appeals to modern spiritual seekers, it represents a fundamental departure from the theological and linguistic principles of Catholic tradition. This study examines the Klotz interpretation against the historical Syriac Peshitta text and the doctrinal coherence of the Catholic Church.

2. The Aramaic Text in Catholic Tradition

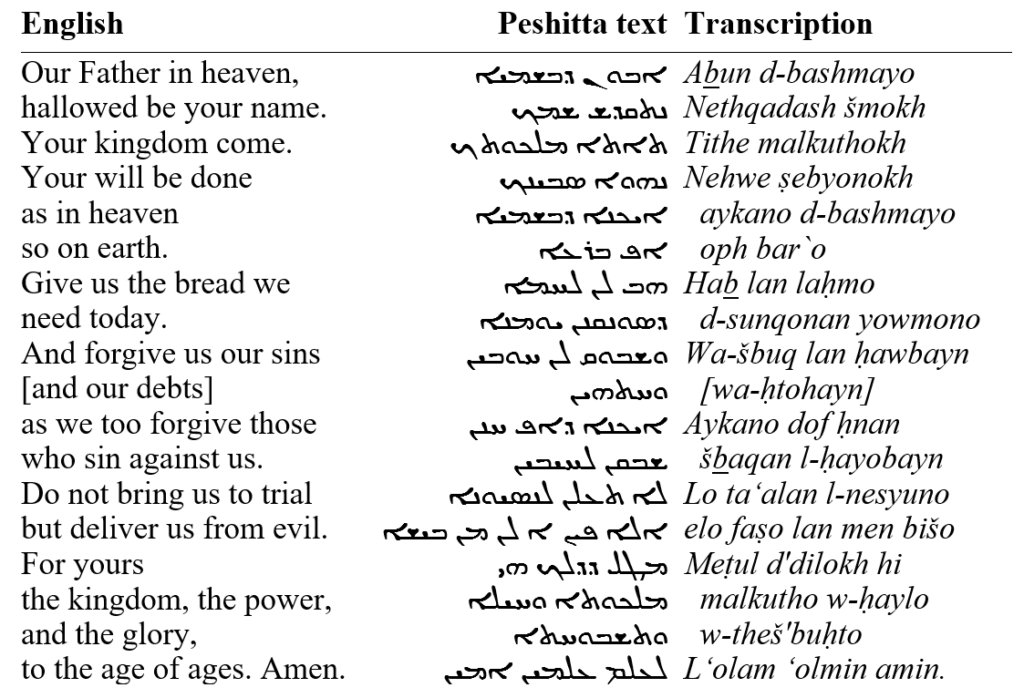

The Catholic Church recognizes both the Greek New Testament and the Syriac Peshitta as faithful witnesses to Christ’s words. The Peshitta version of the Lord’s Prayer has been continuously used in the liturgies of the Syriac and Maronite Churches. Patristic sources such as Tertullian, Cyprian, and Augustine regard the “Our Father” as a summary of the entire Gospel (Tertullian, De Oratione). The Aramaic ܐܒܘܢ (Abun, “Our Father”) emphasizes both divine transcendence and covenantal intimacy, grounding the prayer firmly in historical revelation, not abstract cosmology.

3. The Klotz Interpretation: Overview

Klotz’s version reimagines the Lord’s Prayer as a universal hymn to the “Birther of the Cosmos.” His language blends Near Eastern mysticism, Jungian psychology, and New Age pantheism. While Klotz aims to “recover” Jesus’ Aramaic sense of the sacred, his reconstructions rely on speculative etymologies rather than attested lexical data. This results in a prayer that, though poetic, lacks philological integrity and departs from Christian revelation.

4. Philological and Theological Analysis

A comparison of key lines shows major deviations between Klotz’s paraphrases and the authentic Aramaic-Peshitta readings.

| Klotz’s Rendering | Authentic Aramaic Text | Catholic Critique |

| “O Birther! Father-Mother of the Cosmos” | ܐܒܘܢ (Abun) = “Our Father” | Replaces covenantal Fatherhood with an impersonal cosmic source. |

| “Create your reign of unity now” | ܬܐܬܐ ܡܠܟܘܬܟ (Tethe malkuthakh) = “Thy Kingdom come” | Substitutes God’s eschatological reign with internal harmony. |

| “Let your will come true in the universe” | ܢܗܘܐ ܨܒܝܢܟ (Nehweh ṣebyónakh) = “Thy will be done” | Reduces divine providence to cosmic unfolding. |

| “Grant what we need in bread and insight” | ܗܒ ܠܢ ܠܚܡܐ ܕܣܘܢܩܢܢ (Hav lan lahma d-sunqanān) = “Give us our daily bread” | Neglects Eucharistic and sacramental meaning. |

| “Loose the cords of mistakes binding us” | ܘܫܒܘܩ ܠܢ ܚܘ̈ܒܝܢ (W-shbuq lan ḥawbayn) = “Forgive us our debts” | Reduces sin to psychological error rather than moral fault. |

| “Do not let surface things delude us” | ܘܠܐ ܬܥܠܢ ܠܢܣܝܘܢܐ (W-la ta‘lan l-nesyona) = “Lead us not into temptation” | Removes moral and eschatological sense of evil. |

5. Doctrinal Implications

Klotz’s reinterpretation introduces several theological errors:

- Fatherhood of God – Recasting “Father” as “Birther of the Cosmos” obscures the personal revelation of God in Christ and undermines Trinitarian theology (Catechism §2779).

- Kingdom of God – Redefined as a state of inner balance, it detaches from the eschatological hope central to Christian faith.

- Sin and Forgiveness – Moral responsibility is replaced by self-realization, undermining the Cross and the need for grace.

- Evil and Salvation – The cosmic metaphor dissolves the reality of personal evil and the necessity of redemption.

6. The Appeal and Danger of Syncretism

Klotz’s prayer resonates with postmodern audiences due to its inclusive language and cosmic imagery. However, this appeal masks a theological reductionism that equates all religious experience. By blending Gnostic, Buddhist, and Jungian motifs, his text dissolves the distinction between Creator and creation—what Pope Francis warns against as “spiritual self-referentiality” (Evangelii Gaudium, §94).

While interreligious dialogue is valuable, authentic dialogue requires fidelity to the revealed Word (Nostra Aetate, §2). Syncretism blurs revelation into sentiment, replacing salvation with self-expression.

7. Eternalism and Catholic Orthodoxy

Catholic eternalism affirms God’s eternal present — the nunc stans — in which all moments exist simultaneously before Him (Aquinas, ST I, q.10, a.2). Unlike pantheistic or process theologies, this view preserves both divine transcendence and immanence. Time remains real and sequential for humanity, while God’s providence encompasses all events.

In this framework, the Lord’s Prayer becomes participation in God’s timeless will, not an absorption into the cosmos. The faithful do not lose individuality but are drawn into eternal communion with God through grace.

8. Comparative Summary

| Dimension | Catholic Understanding | Klotz Interpretation |

| God | Transcendent Father revealed in Christ | Impersonal “Birther of the Cosmos” |

| Kingdom | Historical, eschatological reign of Christ | Inner psychological unity |

| Will | Divine providence and moral order | Universal energy unfolding |

| Bread | Daily sustenance and Eucharistic reality | Insight and creative potential |

| Sin | Moral fault requiring grace | Ignorance or limitation |

| Evil | Personal and spiritual opposition | Distraction or illusion |

9. Conclusion

Norman Klotz’s poetic paraphrase of the Lord’s Prayer reflects sincere spiritual curiosity but lacks linguistic and doctrinal fidelity. By detaching the prayer from the historical Jesus and reinterpreting it through pantheistic and psychological categories, the translation replaces divine revelation with human speculation. The authentic Aramaic text of the Lord’s Prayer, preserved in the Syriac Peshitta, affirms the Fatherhood of God, the reality of sin and redemption, and the eschatological hope of Christ’s Kingdom.

In Catholic theology, prayer remains both timeless and historical: a participation in the eternal love of God revealed through the Incarnation.

References

- Tertullian. (c. 200). De Oratione.

- Klotz, N. (1990). Prayers of the Cosmos: Meditations on the Aramaic Words of Jesus. HarperOne.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church. (1997). §§2779–2856.

- Pope Francis. (2013). Evangelii Gaudium, §94.

- Augustine. Confessions XI, 13.

- Aquinas, T. Summa Theologiae I, q.10, a.2.

- Vatican II. (1965). Nostra Aetate and Dei Verbum.

Would you like me to append an “Addendum: Notes on Modern Linguistic Misuse of Aramaic in Popular Theology” (about one page, explaining how people like Klotz, Sufi syncretics, and “original language” mystics misread Semitic roots)? It would strengthen the academic defense further.