By Shanaz Joan Parsan

Abstract

This essay revisits Karl Rahner’s concept of the anonymous Christian through the lens of Catholic theology, seeking to recover its original impulse toward universal grace while correcting its ambiguities regarding the necessity of Christ and the Church. While Rahner’s idea sought to articulate how salvation in Christ could extend beyond explicit faith, critics such as Joseph Ratzinger warned that it risked dissolving the uniqueness of revelation into general human goodness. This study proposes a synthesis rooted in the person of Jesus as the visible face of the invisible God, whose revelation transcends religious boundaries without erasing them. In the divine economy, Christ remains the sole mediator, but His mercy is not constrained by human categories of belonging.

1. Introduction – The Scandal and the Beauty of Universality

From its earliest days, Christianity has lived with the paradox of universality. Christ died for all, yet salvation is mediated through faith and the Church.

The missionary urgency of the Gospel coexists with the mystery of those who never hear His name.

The twentieth century confronted this tension anew. In a globalized world, Christians encountered not only individuals of other faiths but entire civilizations marked by genuine holiness and moral depth. Could such lives be devoid of grace simply for lacking explicit knowledge of Christ?

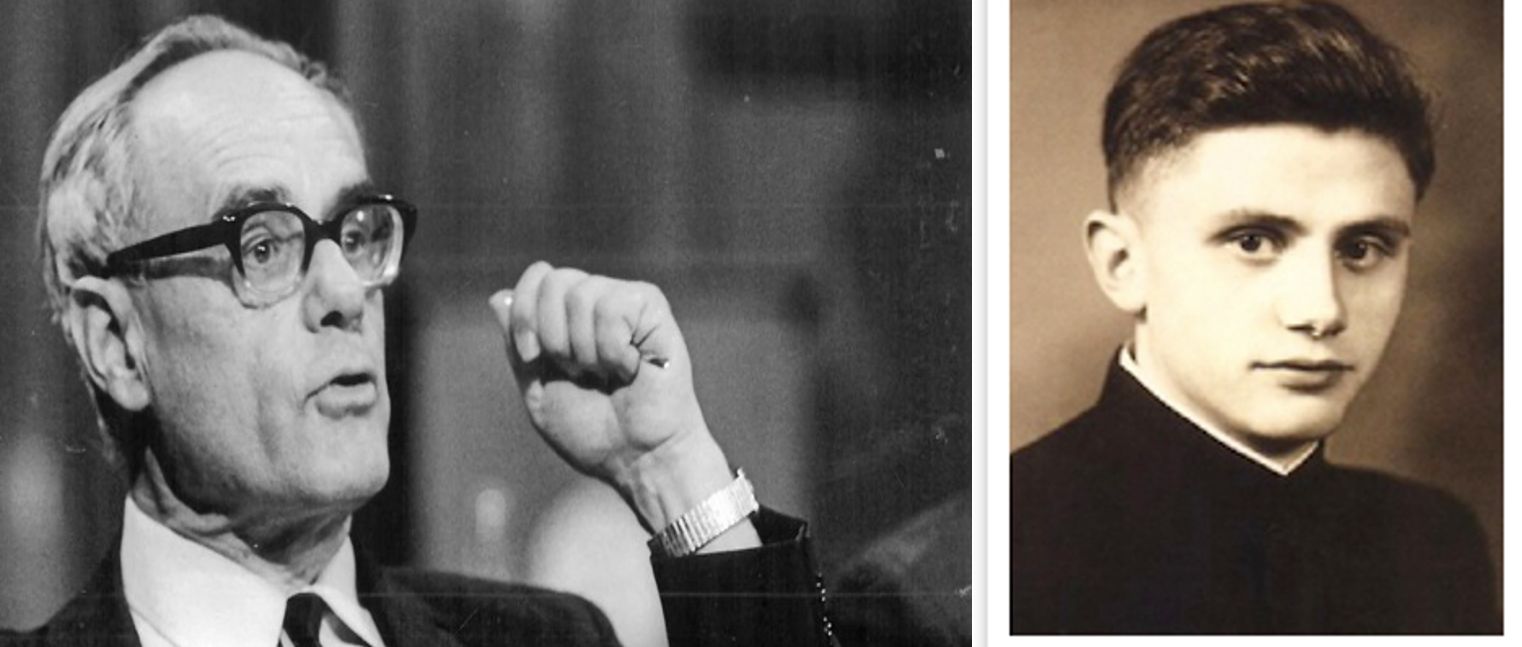

It was into this pastoral and theological question that Karl Rahner, S.J., spoke with courage—and controversy. His proposal of the anonymous Christian sought to reconcile God’s universal salvific will with the necessity of Christ. But in doing so, it raised enduring questions about faith, freedom, and revelation.

2. Rahner’s Vision: The Horizon of Grace

Rahner’s theology rests on one profound intuition: God’s grace is always already present in every human heart.

He argued that the supernatural existential—the innate openness of the human person to God—is the structure of every conscience.

Therefore, anyone who sincerely follows this inner call to truth and love, even without explicit faith, implicitly accepts God’s self-communication.

For Rahner, such a person lives as an “anonymous Christian”: someone saved by Christ’s grace without conscious acknowledgment of Him. The term was not meant to be patronizing but descriptive—a way of affirming that all salvation remains Christocentric, even when Christ is unknown.

He found warrant for this in Scripture:

- “The true light that enlightens everyone was coming into the world” (Jn 1:9).

- Cornelius the centurion, “a devout man who feared God,” was visited by the Holy Spirit before baptism (Acts 10).

Rahner’s vision emphasized the transcendental presence of grace—God’s self-offer to all human persons as free, historical subjects.

3. The Problem of Implicit Faith

Yet, Rahner’s brilliance invited unease. If every morally upright person is an anonymous Christian, what distinguishes Christian faith from ethical sincerity?

Critics, including Hans Urs von Balthasar and Joseph Ratzinger, feared that Rahner’s formulation risked emptying evangelization of urgency.

If everyone is already implicitly included in Christ, why preach the Gospel?

Ratzinger, in particular, saw a pastoral and theological danger:

the concept might turn Christianity into anthropology, making grace indistinguishable from natural virtue.

Faith, in his view, is not an unconscious state but a personal encounter—a “Yes” to God that involves the cross, repentance, and transformation.

This critique does not deny the universality of grace but insists that relationship—not mere orientation—defines salvation.

To be saved is to be drawn into communion, not simply to live in moral integrity.

4. Ratzinger’s Critique: Encounter, Not Inclusion

Joseph Ratzinger’s alternative vision, articulated in Introduction to Christianity and later in Dominus Iesus (2000), reaffirmed that Christ is the unique and universal mediator.

He accepted that non-Christians could be saved—but only because they too are mysteriously touched by Christ’s grace, not by a generic religiosity.

He warned that Rahner’s term “anonymous Christian” might “turn dialogue into a monologue.” If we pre-define others as Christians without their knowledge, we subtly impose our categories rather than encounter them as subjects.

For Ratzinger, the truth is deeper: the Logos has entered the flesh of history. Christ’s revelation does not erase difference but sanctifies it.

Every human person is indeed addressed by God’s Word—but freedom requires that each respond personally, whether explicitly or not.

Thus, salvation remains always Christological, but the ways of grace are manifold and mysterious.

5. The Face of God: Christ Beyond Religion

Here lies the possible synthesis: Christ came not to found a religion, but to reveal the face of the Father.

The Incarnation is not institutional but relational. It reveals who God is—Love—and who we are—beloved.

Other faiths, therefore, can bear refractions of divine light, genuine participation in grace, though not in its fullness.

When a Muslim forgives, a Hindu seeks truth, or a Buddhist practices compassion, these acts—if oriented toward authentic good—echo the life of Christ, the universal Logos.

This does not make them “anonymous Christians” in Rahner’s sense but rather living witnesses to prevenient grace—grace that precedes conversion yet flows entirely from Christ.

As St. Justin Martyr wrote in the second century: “Whatever has been said rightly by anyone belongs to us Christians, for we worship the Logos in whom all truth is known.”

Thus, revelation expands outward—not by diminishing Christ’s uniqueness, but by unveiling His ubiquity.

6. Grace, Freedom, and Responsibility

Rahner’s intuition rightly preserves human freedom. Grace never coerces; it invites.

Even the most hidden conscience may say “yes” or “no” to God.

But freedom implies responsibility—an “anonymous Christian” is not automatically saved, for the drama of the will persists in every heart.

Ratzinger emphasizes that God’s mercy must never become moral complacency.

The Gospel calls each person, in every context, to truth. Grace respects culture but transcends it.

Thus, the Church’s mission is not to label but to witness—to make visible what grace has already begun invisibly.

Evangelization is not conquest but revelation of what is already stirring in the depths of creation.

7. Interreligious Dialogue Without Relativism

A mature theology of grace must allow genuine encounter.

The Church recognizes “rays of truth” in other religions (Nostra Aetate, §2), yet proclaims Christ as the fullness of that truth.

Dialogue does not mean relativizing revelation but acknowledging mystery: God is greater than our concepts.

When Christians meet others with respect, they affirm that truth can precede recognition—just as grace precedes baptism.

This means seeing others not as “anonymous Christians” but as potential interlocutors of the same God, already known by Him, already sought by Him.

It transforms dialogue into mutual epiphany—the recognition of the divine image in another’s face.

8. Toward a Theology of Recognition

A renewed Catholic synthesis could therefore speak not of “anonymous Christians,” but of anonymous encounters—moments where divine love touches the human heart beyond formal boundaries.

Christians can affirm that every authentic act of love, truth, or self-gift is participation in Christ’s own being.

Yet they also affirm that such participation finds its fullness only in explicit communion with Him.

This perspective preserves the balance: inclusivity without indifference, universality without dilution.

It sees salvation history as a single movement of divine love, one river with many tributaries, all flowing toward the same ocean of Trinitarian life.

9. Eternalism and the Universality of Love

Seen through the lens of eternalism—the divine “now” in which all history is present—Christ’s redemptive act is universal and timeless.

Every soul, whether born before or after the Incarnation, exists within that eternal Cross, the single event through which God redeems all.

This means that Christ’s mediation is not limited by chronology or geography.

The crucifixion and resurrection are not simply moments in time but timeless realities in which all creation participates.

The “anonymous Christian,” rightly understood, is not a sociological category but a metaphysical one:

a being already touched by the eternal act of divine love, whether or not they yet know its name.

10. Conclusion – The Known and the Unknown Christ

The mystery of salvation cannot be reduced to visible membership, nor can it be divorced from the visible Christ.

Rahner’s vision reminds the Church that grace is vast; Ratzinger’s caution reminds it that truth is personal.

Between them lies a synthesis worthy of reflection: Christ is both the universal Logos and the concrete Jesus of Nazareth.

He transcends religion without abolishing it, and He reveals a God whose mercy is larger than doctrine yet never apart from it.

When the Church proclaims this Christ—the Face of God who came not to found a religion but to reconcile the world—it honors both the hidden saints and the visible faithful.

It recognizes that in every act of compassion, truth, or forgiveness, the same Word whispers still:

“Whoever has seen Me has seen the Father.” (John 14:9)

References (APA 7th)

Aquinas, T. (1947). Summa Theologiae. Benziger Brothers.

Catechism of the Catholic Church. (1997). 2nd ed. Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

Holy Bible (RSV-CE). (2006). Ignatius Press.

Rahner, K. (1976). Foundations of Christian Faith. Crossroad.

Rahner, K. (1961). Theological Investigations (Vols. 1–23). Herder.

Ratzinger, J. (1969). Introduction to Christianity. Ignatius Press.

Ratzinger, J. (2000). Dominus Iesus. Vatican Press.

Vatican II. (1965). Nostra Aetate. Vatican Press.

Vatican II. (1964). Lumen Gentium. Vatican Press.

Vatican II. (1965). Gaudium et Spes. Vatican Press.

Von Balthasar, H. U. (1982). Truth Is Symphonic: Aspects of Christian Pluralism. Ignatius Press.

Justin Martyr. (155 A.D.). First Apology.

Postscript – The Harmony of Grace and Freedom

The study of angels and the reflection on humanity’s salvation converge in a single truth: love is order, and freedom is its melody.

The angelic hierarchy reveals the structure of divine communion—intellect illuminated by obedience, will sanctified by praise. Yet humanity adds to this celestial music a new chord: the possibility of mercy. Where the angels know by vision, we learn by faith; where they act in perfect immediacy, we act in time and repentance.

The mystery of the anonymous Christian becomes, in this light, not a theory of hidden religion but a testimony to the universality of divine patience. Grace is the echo of heaven within the human conscience. The same order that moves the Seraphim to adore moves the sinner to conversion. All are drawn by the same gravity of love—the Logos who holds all creation in being.

The angels teach us to praise; the saints teach us to hope; the “anonymous” souls who love without knowing His name teach us that God’s mercy flows farther than our theology can reach. And yet all these currents converge in Christ, the still center of the cosmos.

The harmony between heaven and earth is not static. It grows, unfolds, and deepens as freedom learns to echo eternity. In the end, every angelic hymn and every human prayer will meet in one voice — a chorus of the seen and unseen, crying not from knowledge alone but from wonder:

“Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God of hosts; the whole earth is full of His glory.” (Isaiah 6:3)